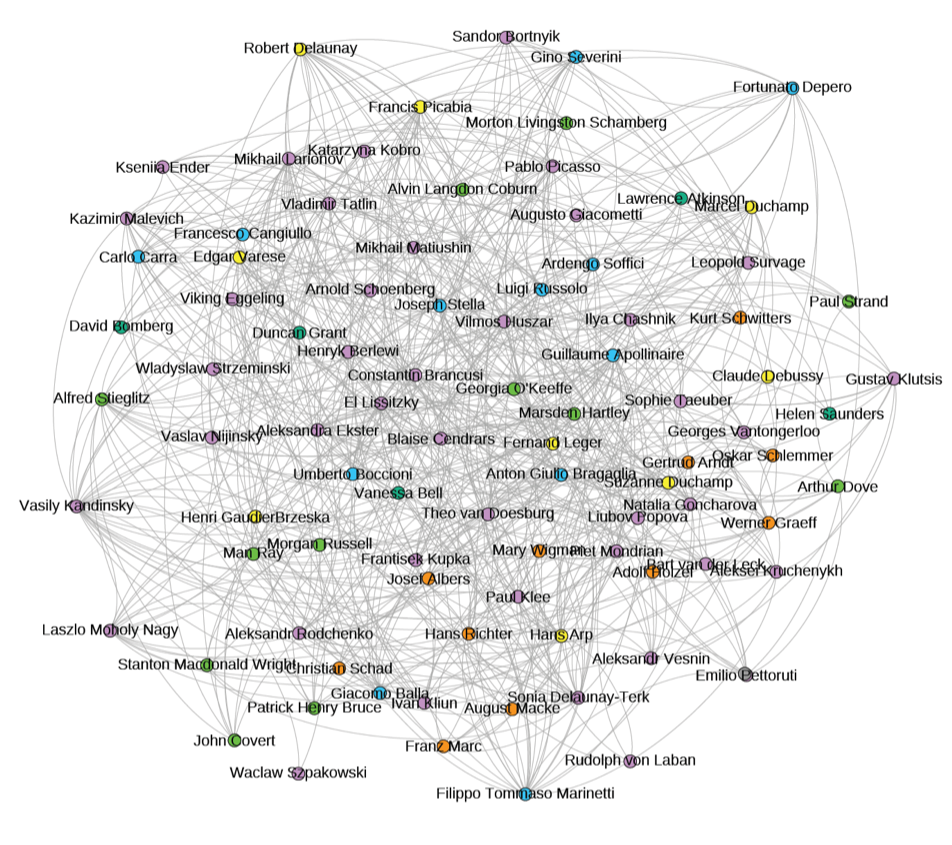

In a 2012 exhibition about the birth of abstraction at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curators highlighted the way that the artists may have influenced one another. Titled “Inventing Abstraction: 1910–1925,” the show illustrated over 80 artists’ radical departures from the traditions of representational art, and opened with a large diagram depicting their network to show who knew each other (an interactive version of which is online), with the most connected, like Pablo Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky, toward the center.

While working on the show with her colleagues, exhibition curator Leah Dickerman (now MoMA’s director of editorial and content strategy) was influenced in part by a course she had taken with Columbia Business School professor and Chazen Senior Scholar Paul Ingram, which was about how curators can use their professional networks to achieve success. Ingram helped to develop an early iteration of the network of early pioneers of abstraction, and later, he used the same data to embark on a new investigation.

Ingram and his colleague Mitali Banerjee, of HEC Paris, used MoMA’s findings to examine the role that creativity and social networks played for these artists, in relationship to the level of fame they achieved. In a 2018 paper, they relayed their findings—including that for successful artists, making friends may be more important than producing novel art.

The study

Andy Warhol, Photograph of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bryan Ferry, Julian Schnabel, Jacqueline Beaurang, Paige Powell, and Others at a Party at Julian Schnabel's Apartment, 1985, 1985 Hedges Projects

Ingram and Banerjee started their study by quantifying the fame, creativity, and social network of the artists in “Inventing Abstraction.” To determine each artist’s renown, they turned to Google’s database of historical texts in French and English (given that the artists were primarily living in France and the U.S.), and recorded the number of mentions each artist had between 1910 and 1925. They were looking at fame in terms of how well-known the artists were beyond their own social circles, Ingram noted, “and we’re essentially saying [that] how often you show up in the written word is an indicator of that.”

To examine the artists’ social networks, they relied on MoMA’s research, which was based on sources like biographies and artists’ letters to identify relationships. Ingram and Banerjee analyzed the artists’ social circles, which also involved data on each artist’s nationality, gender, age, and location, as well as the media they were using and the schools they attended. (They didn’t look into the artists’ exhibition history or the market for their work, though Banerjee’s future research may include such factors, Ingram said.)

In order to understand the creativity of the artists’ work, they employed two methods. First, they used machine learning to analyze and rate the creativity of thousands of artworks by the relevant artists; the computer program rated how unique works are in comparison to a set of representational artworks from the 19th century. They also asked four art historians to rate artworks by each artist for their creativity, based on factors like originality and innovation. (They found that the scores artists earned from machine learning and art historians were positively correlated.)

What it found

Peer network of the artists in “Inventing Abstraction.” Courtesy of Paul Ingram and Mitali Banerjee.

While past studies have suggested that there is a link between creativity and fame, Ingram and Banerjee found, in contrast, that there was no such correlation for these artists. Rather, artists with a large and diverse network of contacts were most likely to be famous, regardless of how creative their art was.

Specifically, the greatest predictor of fame for an artist was having a network of contacts from various countries. Ingram believes this indicates that the artist was cosmopolitan and had the capacity to reach different markets or develop ideas inspired by foreign cultures. The “linchpin of the network,” he added, was Kandinsky. They also found that famous artists tended to be older, likely because they were already famous as abstraction was emerging, Ingram explained.

In terms of creativity, they found that neither the computational evaluations nor the art historians’ expert opinions were strong indicators of an artist’s renown. In other words, if an artist had high creativity scores, they were not necessarily famous.

“An important implication of the paper is to show that diverse networks matter not only as a source of creativity…but could mean other benefits,” Ingram said. “That even aside from creativity…the artists benefit from the cosmopolitan identity.”

What it means

Wassily Kandinsky with a group of artists from the Blue Rider. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Given the modern imperative to meet new people and network across professional industries in order to open oneself up to career opportunities and advancement, Ingram and Banerjee’s findings aren’t surprising. However, they do offer important reminders—that we won’t become famous in a vacuum and should seek to diversify our social circles.

By way of illustrating the findings, the researchers pointed to the example of two artists among the group, Vanessa Bell and Suzanne Duchamp. While neither artist is a household name, they shared similar backgrounds had very famous siblings (Virginia Woolf and Marcel Duchamp, respectively), and had similar creativity scores—but Bell was more famous.

“Both artists were part of influential artists’ groups—Suzanne Duchamp was part of the Dada circle while Vanessa Bell was part of the Bloomsbury group,” the authors wrote. “Yet Duchamp’s social circle was confined to the Dada artists; in fact, even within this circle, her closest friends were her brother Marcel, her husband Jean Crotti and the artist Francis Picabia, a family friend. In contrast, Vanessa Bell’s social world encompassed the Bloomsbury group, a broad swathe of artists who were part of the London Group, collectors and patrons located outside England such as Gertrude Stein as well as theatre producers and artists associated with Sergei Diaghilev’s Les Ballet Russes.” Ultimately, Bell’s more diverse circle correlates with her greater fame.

“What we know from different kinds of research is that diversity in networks feeds creativity, which is an important thing for artists, as well,” Ingram explained. Having such a network, he added, meant that “you could kind of be positioned in a market, and may be more interesting and worthy of attention, if you are connected to a diverse set of others.” And even though the study focused on a specific, century-old context, he predicts that the findings ring true for artists today.

Casey Lesser is Artsy’s Lead Editor, Contemporary Art and Creativity.