Sue Davies, the founder of the Photographers' Gallery standing at its entrance

on Great Newport Street, between Leicester Square and Covent Garden.

The institution's director Brett Rogers has selected five key shows from the past five decades.

“Everyone put pressure on her to call it the Photography Gallery,” says Brett Rogers, the director of the Photographers’ Gallery in London. “But she said no, it’s a place for photographers, we want them feel comfortable here.” The “she” in question was Sue Davies, the founder and first director of the Photographers’ Gallery, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

The Photographers’ Gallery was the first public institution dedicated to photography in the UK. In the lead up to its formation, Davies had been working at the Institute of Contemporary Art where she met several photographers who like her felt that London was in need of a space dedicated to the medium. One of her key goals was “to gain recognition for photography as an art form in its own right”. Davies drummed up support for the venture and raised funds, which included remortgaging her own house, before finding a space on Great Newport Street, near Covent Garden. And on 14 January 1971, the Photographers’ Gallery was born.

“[Davies] wanted to create a space for photographers who aspired to be artists and also for photographers who were photojournalists and trying to find their way within the industry, within editorial and advertising,” Rogers says. “That was quite surprising. She wanted to both recognise it as an art form but also to acknowledge the very important roles played by applied photography: magazines, print press, medicine, Nasa photography, picture postcards.”

The Photographers' Gallery moved to its new home just off London's Oxford Street in 2012

In the first year alone, the new gallery hosted 19 exhibitions. Among these were shows of photojournalism; landscapes; Polaroids by Andy Warhol; Zoe Dominic’s pictures of ballet dancers; a Jacques Henri Lartigue survey; sepia prints of London in the 1870s; and a group show of erotic photography. “All I ever say is, her view was very eclectic and Catholic and that was a good thing,” Rogers says. “[Davies] embraced the whole breadth, and we do today.”

Davies was director of the gallery for two decades, stepping down in 1991. She was followed by Sue Grayson Ford, Paul Wombell and in 2005 Rogers took over. The gallery moved to its new space in central London, just off Oxford Street, in 2012. For the past eight years Rogers has been planning the Soho Photography Quarter, an outdoor pedestrianised zone around the gallery “where you can see photography 24/7 free of charge”. The area underwent a soft launch in September with the final completion and formal opening planned for February 2022. “It’s going to be safe, and beautifully lit, welcoming and not smelly,” says Rogers, referring to what was often a urine-scented alleyway.

Rogers took some time away from planning the future of the institution to cast her mind back to its past and select five exhibitions that have defined the Photographers’ Gallery.

Five key exhibitions at The Photographers’ Gallery

The private view for The Concerned Photographer, the first exhibition at The Photographers Gallery

The Concerned Photographer (13 January-13 February 1971)

Featuring: Werner Bischof, Robert Capa, Leonard Freed, André Kertész, David Seymour, Dan Weiner

The first exhibition at the newly formed gallery was an unplanned one. “Although Sue [Davies] wanted to do a show on Civil Rights photography, this came into her lap at the right time when we had to open,” Rogers says. The exhibition was organised by the International Fund for Concerned Photography in New York, founded by Cornell Capa, and which later spawned the International Center of Photography. “This was the heyday of Magnum and the photo agencies, so [the show] reflected the importance of photojournalism,” Rogers says. Among the highlights were works by Robert Capa—“there were some unusual ones by him”—and David Seymour’s “beautiful images of children during the war in Poland”.

The exhibition also experimented with new curatorial ideas, “transferring what had always been seen in print and in magazines, onto the gallery wall,” Rogers says. “That had never been done in the UK really. We very successfully did big blow ups [with] small images framed.” Rogers adds that the exhibition “set the tone” for the Photographers’ Gallery and led to many photojournalism and reportage shows over the decades, including work by, among others, Margaret Bourke-White, Elliott Erwitt, Eugene Smith, Bruce Davidson, Werner Bischof and Sebastião Salgado. “All the great names,” Rogers adds.

Installation view of Five Years with the FaceCourtesy of The Photographers’ Gallery Archive

5 Years with The Face (18 April-17 May 1985)

Featuring: Anton Corbijn, Chalkie Davies, Jill Furmanovsky, Mike Laye, Robert Mapplethorpe, Jamie Morgan, Sheila Rock and Carol Starr

The now legendary magazine The Face was at the height of its powers in the mid-1980s, covering youth culture and fashion its unique style. The exhibition included work by 37 photographers, including Anton Corbijn, Jill Furmanovsky and Robert Mapplethorpe. One of the key elements that it explored was the importance of the stylist in fashion and commercial photography. “Fashion photography is very collaborative; it’s not like most other independent photography,” Rogers says. “They always work with stylists and art directors. [The exhibition] very much investigated the role of Ray Petri, this incredible stylist from the 80s who subverted the whole way you took a fashion photograph.”

The graphic designer Neville Brody, who was the magazine’s art director at the time, designed the exhibition and its distinctive poster. Rogers adds that there is “a lovely link to our 50th anniversary” as Brody recently got back in touch with the gallery offered to design its 50th anniversary logo, because he had such “fond memories” of the show. The exhibition paved the way for later exhibitions by trendy fashion photographers such as Juergen Teller and Corinne Day, Rogers says. “We’ve always prioritised [fashion exhibitions] because we know young people love fashion. We’re just off Oxford Street, so why wouldn’t we?”

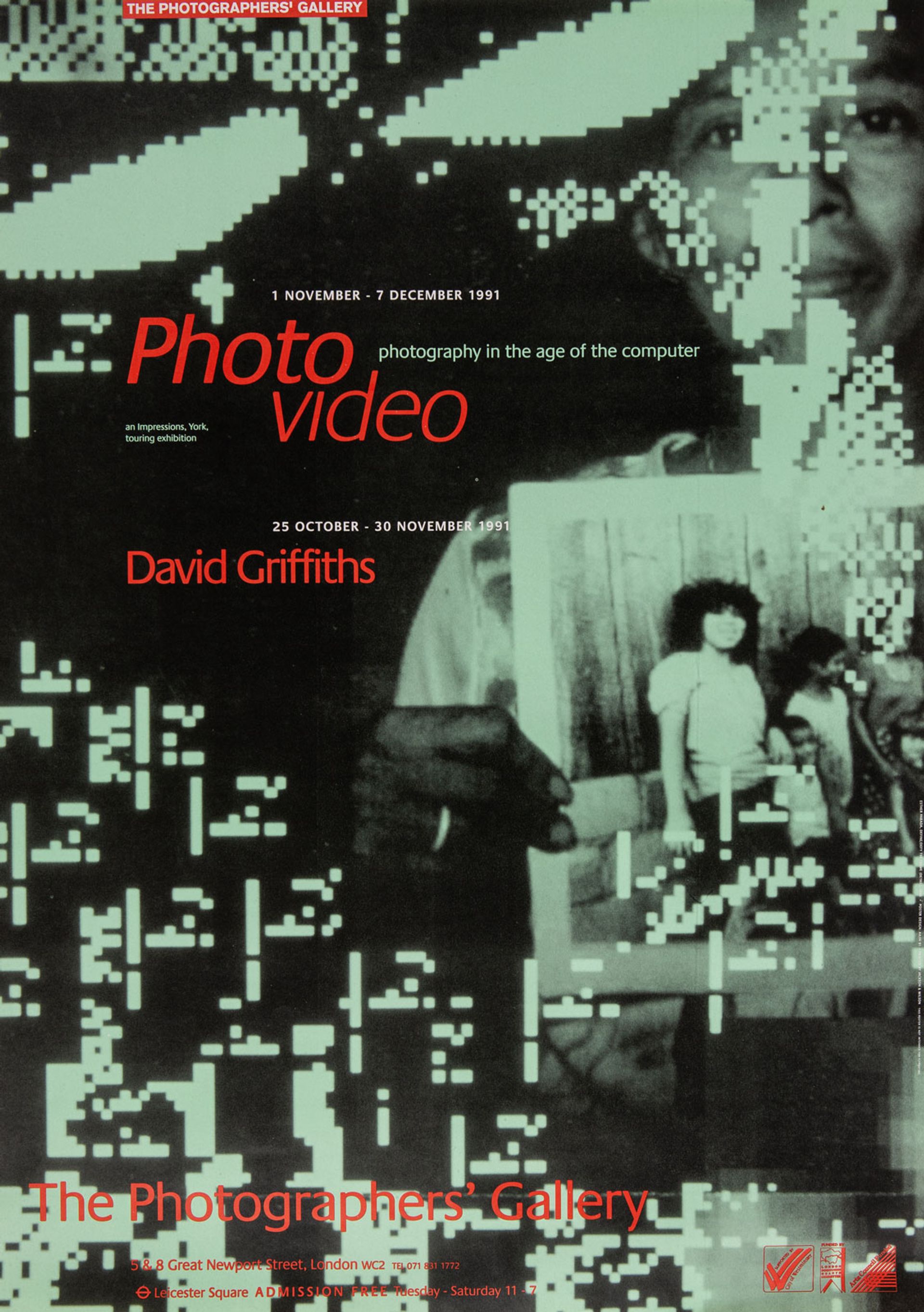

The poster for the Photovideo: Photography in the Age of the Computer exhibition

Photovideo: Photography in the Age of the Computer (1 November-7 December 1991)

Featuring: Susan Boyce, Susan Hardy, Brian Harris, Graham Howard, Pedro Meyer, Clinton Osbourne, Esther Parada, Philip Benson & David Perret, Keith Piper, Simon Robertshaw and Kativa Sharma

“The gallery was full of video screens and electronic buzzing and datasets,” Rogers says. It was an exhibition that showed how photography was going “from the darkroom to the computer screen—and how that change was already happening already in the 90s”. The exhibition was curated by Rogers’s predecessor Paul Wombell and Steven Bode, who runs Film and Video Umbrella. “What they recognised was the early impact of new technologies on the image,” Rogers says. “It was influenced by Tiananmen Square and all those images of the tanks and the blurry images and pixilation that came down through video stills.”

As well as examining the beginnings of the digital culture that we take for granted today, it also looked at who made and stored images and the use of big data. It explicitly asked “what are the implications for society?” Rogers says. “They looked at mass surveillance, the role of the military in creating images, and datasets—even in ’91. We think this was a prescient exhibition because nobody was talking about that.”

Taryn Simon's exhibition An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar showing one of her works documenting a nuclear waste storage facilityCourtesy The Photographers’ Gallery Archive

Taryn Simon: An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (12 September-11 November 2007)

Featuring: Taryn Simon

“We have always had a very big commitment to promoting women artists and somebody who really set the bar high in interrogating documentary [photography] and really put conceptual photography on the map, is Taryn Simon. We were the first to show her [in the UK],” Rogers says. The impact of the topics covered by the American photographer marked many who saw the show. “Doesn’t it stay with you? She went into a forensic laboratory, she documented a Palestinian woman having a hymen reconstruction, [she photographed] inside the CIA, [showed] the big internet cables coming up from the sea. It was one of the most staggering exhibitions ever. She just struck a new chord with where photography could go.”

Simon went on to have a major shows around the world, branching out from photography with notable performance installations such as An Occupation of Loss (2016). There was a real “conceptual richness” to the show at the Photographers’ Gallery, which “reset the bar”, Rogers says. And led to “photographers thinking differently: what is photography capable of? What can it uncover?”

Installation view of Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s© Kate Elliot

Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s: Works from the Verbund Collection (6 October 2016-15 January 2017) Featuring: VALIE EXPORT, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman and Martha Rosler, among others

“That show had everybody from Cindy Sherman to Hannah Wilke, to our lovely Alexis Hunter who died shortly after,” Rogers says. “As well as many unknow names.” The exhibition of 48 female photographers from the Verbund Collection in Vienna focused on work made during the 1970s that dealt with political issues such as the patriarchy and sexism. As well as photography, the show also include collage works, films and videos. Rogers says that with such a show it was important to see the works in the exhibition rather that in photobooks. “It’s the visceral quality; their work is so hard hitting. And some of them are stitched and you can’t really see that in a book.”

“To younger photographers coming to our gallery, they may have heard their names but they had never seen their work,” Rogers says. “[It was] really radical, provocative, political work. And I really think it shook them up; it had a big impact.”